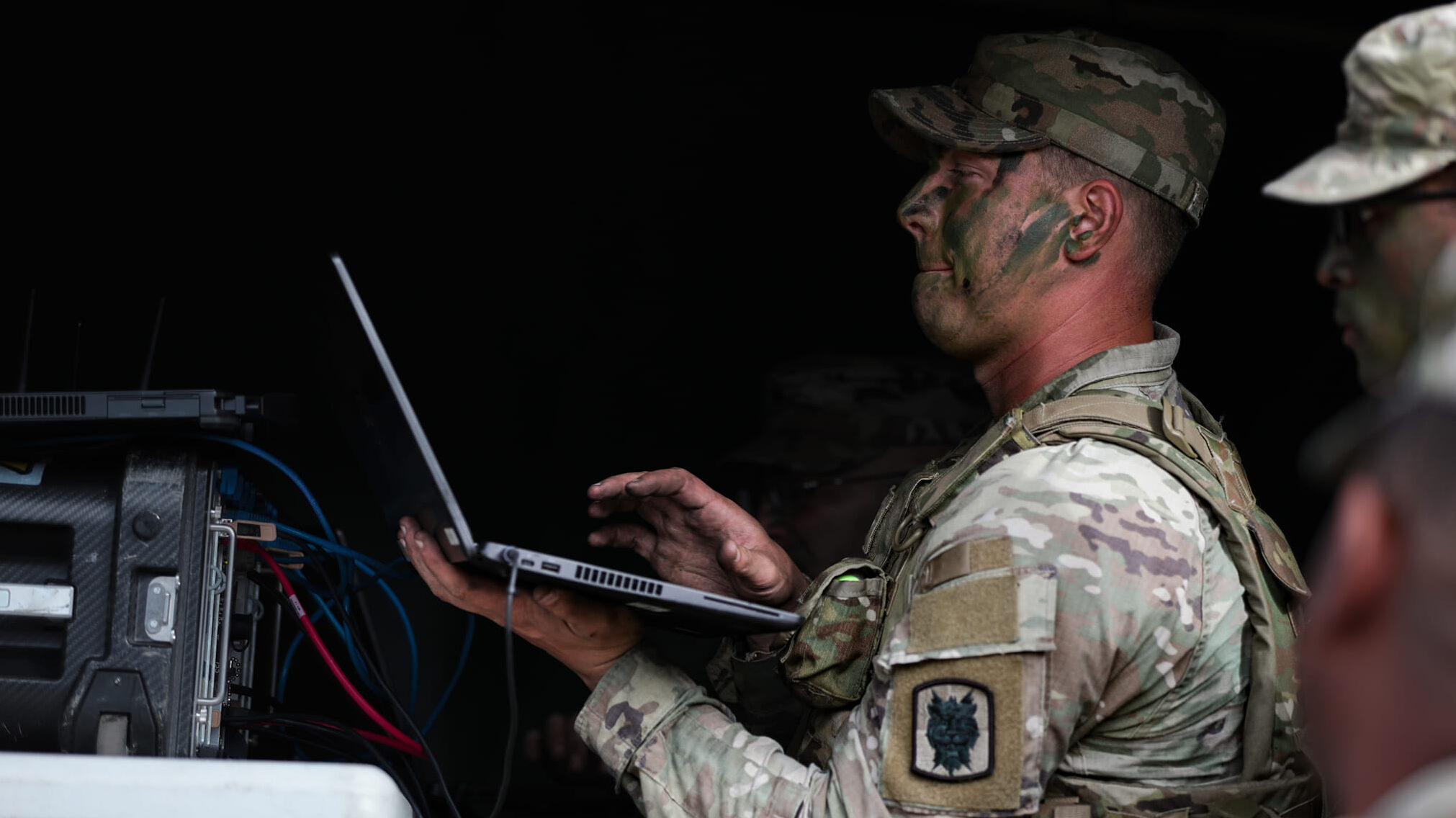

The ultimate goal of the Army’s Unified Network is to give soldiers the same network capabilities while deployed as they have at posts, camps, and stations. (US Army.)

To discuss the US Army’s progress in developing a layered terrestrial- and space-based tactical network that will be a main building block for Joint All Domain Command and Control, Breaking Defense talked with Col. Shane Taylor, project manager, Tactical Network, Program Executive Office Command Control Communications-Tactical (PEO C3T), and John Anglin, technical management division chief for PM TN.

Breaking Defense: A recent Army article quoted US Army Deputy Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. John Morrison as saying: “The Army’s Unified Network is the Army’s contribution to JADC2, and at the core of the unified network is space.” The unified network almost sounds like a concept of operations like Joint All Domain Command and Control. But it’s more than that. Describe what is meant by the “unified network.”

Anglin: The two main components of the Unified Network are the Integrated Tactical Network and the Integrated Enterprise Network, ITN and IEN. For ITN, we’re fielding kit from the company up through the battalion and brigade to division, with other maneuver type elements sprinkled in.

That’s supporting everything from the base band perspective for each of the enclaves that they need to support. We have our own transport network called the Unified Transport Network that is, essentially, colorless. That is what we’re using to interconnect all of the DoD teleports, the regional hub nodes. It’s the fabric that’s stitching all this together. Then there’s user enclaves that connect into that transport network.

The flexibility there is to drive toward [being] transport agnostic, where you can take a unit’s base band component and plug it into commercial internet, a commercially provided terminal, or one of the program-of-record terminals that we field. It gives them flexibility to reach into tactical and strategic.

Col. Shane Taylor, program manager, Tactical Network, US Army PEO C3T.

Taylor: From an Army perspective, there are deliberate gaps from where we came from between those formation types. That puts a lot of complexity down at the user level.

It also causes impacts when a unit goes from point A to point B. Depending on where point B is, it could result in them quite frankly having to sometimes even re-image their systems to be able to access the DODIN in that new location.

Where the Army is going is an attempt to converge those networks, both from a technical and policy perspective, so that a soldier using the system at post, camp, and station can also use that same system in a deployed environment.

That is the impetus behind the Unified Network approach — common standards and policy. From a hardware perspective, it’s routers, switches, encryptors.

To your point, this is not just a concept. There’s definitely material solutions behind all of it. It’s a unifying effort to get us all rowing in the same direction in some of those solutions and how we implement them.

Breaking Defense: And what about the importance of space in the Unified Network?

Taylor: As a signaleer, one of your responsibilities is to develop what we call a PACE plan [primary, alternate, contingency, and emergency plans for resilient communications]. A signaleer is going to attempt to maximize all the options available to them, so space and terrestrial are key players.

I wouldn’t necessarily prioritize one over the other in the aggregate; you probably would on specific missions where SATCOM would be your primary depending on where you’re at. There are other missions where line of sight may be your primary. Other missions where fiber may be your primary. They’re all key. Every one of those pathways — whether it be line of sight, beyond line of sight, fiber, host nation, 5G, SATCOM, and LEO, MEO, GEO — are part of this Unified Network approach.

The challenge for us is how we bring all that capacity and capability to the edge, seamlessly and simply. That’s the impetus behind where we’re going from a Unified Network approach.

The Army’s Unified Network strives for transport agnostic links so a component can plug it into commercial internet and various terminals. Photo courtesy of the US Army.

Breaking Defense: Much of the emphasis of JADC2 is on the kill chain and precision fires, with less attention paid to the command and control aspect. How will the Unified Network let leadership not only command but also have control through communications — even in a contested environment?

Taylor: One of the challenges historically and why there’s been this bit of divide, whether artificial or not, between the strategic and the tactical, is the unique use case from a tactical environment that we used to call a DDIL [denied, degraded, intermittent, or limited] or DIL [disconnected, intermittent, limited] environment. You have to be able to operate with challenges to comms at times, whether it’s jamming, lack of available fiber, geography impacting your line of sight, or host-nation spectrum restrictions. There are a lot of challenges in the tactical space. You have to create an architecture and a configuration that could mitigate the issues associated with that DIL environment.

As we move forward and start enabling things like cloud capabilities and get after the demand signal for constant transport, it hearkens back to our previous discussion about not putting all of our eggs in one basket. We’re going to need all these different pathways.

We talk about PACE, but we need to add some letters at the end of that at some point because of the added links that we’re trying to get in there. There’s less of an acceptance of having a DIL environment in a tactical space. We have to up our game to enable assured, resilient transport in the tactical space.

Breaking Defense: You mentioned that DDIL and DIL were not terms you used anymore. Is there a new term for denied and contested environments?

Taylor: We still use the term. It’s a term that at some point we need to try to work our way out of. What I mean by that is, the more options, the more links that we can provide, the more tools like auto-PACE that enable us to do cross loading, [and other] efforts that are underway, our goal should be to work our way away from that term.

It’s still a term that’s out there. You can have the best SATCOM system in the world but if an adversary puts up a certain type of jammer, you’re not getting out. If the fiber gets cut or you’ve got geography limitations, you’re not going to be able to use it.

There are unique challenges in the tactical space that we don’t see on the enterprise side with posts, camps, and stations, and unique implementations that we have to pay attention to. Our goal is to give them enough options moving forward from the perspective of capability capacity and link aggregation perspective that we work our way away from that term.

John Anglin, chief engineer, PM Tactical Network, PEO C3T, US Army.

Anglin: We want to make it so that the soldiers can fight with the network versus fighting the network. They have other things they have to soldier and do. Working around DDIL or other scenarios shouldn’t be something they have to worry about.

Taylor: The challenge that we’ve given our engineering teams and industry partners is that we want to add all this capability and capacity, but we want you to do it with less kit and keep it simple. That’s because you’ve got general-purpose users having to employ these systems. The signal fleet has been adjusted and a lot of them have been put in different formations for various reasons. The result is you could have a general-purpose user having to implement.

Again, it’s an opportunity for us to focus our limited resources on capabilities that add to everything that we’ve been talking about. But it doesn’t do us any good if it comes with an extensive amount of training and complexity that soldiers won’t be able to install, operate, and maintain.