Ukrainian military prepare a mortar round for firing on September 25, 2023 in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. (Taras Ibragimov/Suspilne Ukraine/JSC “UA:PBC”/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images)

WARSAW — Last week’s European Council meeting in Brussels included attempts to forge unanimity among the 27-state bloc to reinforce Europe’s dedication to backing Ukraine against Russia’s invasion.

The final document from those meetings was headlined by a statement that “Ukraine is a priority and will remain a priority.” Other language includes a pledge to “continue to strongly support Ukraine for as long as it takes, including by economic, humanitarian, military and diplomatic means,” and stating the members “will continue to provide sustainable military support to Ukraine” for the duration of the conflict.

But while there appeared to be unity on paper, it was hard to ignore recalcitrant positions of EU members Hungary and Slovakia. The latter’s newly elected Prime Minister, Robert Fico, had promised an end to his nation’s military aid to Ukraine and halt any further sanctions on Russia. His pro-Russian position is in line with the previous stance by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who now appears to have an ally in the quest to maintain friendly ties with Moscow.

Meanwhile, politics in Washington are becoming messier. After weeks of being unable to operate without a Speaker of the House, the US Congress now has to debate not just how to keep the US government open come mid-November, but the fate of a $105 billion supplemental request from President Joe Biden, which includes over $60 billion for Ukraine.

These fault lines are part of a growing political headache for Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky as he vies to maintain the current level of military aid to his beleaguered nation, at a time when public support in many nations — including the US — seems to be fading after 18 months of conflict. But there is another stressor on Ukraine’s defense: even if countries can keep their politics aligned on support Kyiv, nations are signaling it will become harder and harder to deliver weapons to Ukraine’s arsenal.

Earlier this month Adm. Rob Bauer of the Royal Netherlands Navy told the 10th annual meeting of the Warsaw Security Forum (WSF), “the bottom of the barrel is now visible.” Bauer is the chair of the NATO Military Committee and the alliance’s most senior military official.

“We give away weapons systems to Ukraine, which is great, and ammunition, but not from full warehouses. We started to give away from half-full or lower warehouses in Europe” and those stores are now running low, Bauer told the forum.

Bauer was not the only official at the Forum, which ran Oct. 3-4, to raise concerns. But his phrasing, and the fact that he has deep insight into NATO-wide coffers, was enough to raise eyebrows. It was especially notable that his comments came just after the UK’s Telegraph newspaper cited an unnamed “senior military chief” saying Britain has “given away just about as much as we can afford” to Ukraine.

Asked about that story by Breaking Defense during a recent visit to Washington, UK Defence Secretary Grant Shapps pushed back, saying “That story’s just not entirely correct. In fact, immediately after it … I went to Brussels to the Contact Group and announced another £170m of various different types of aid, including international funding that the UK has helped pull together.

“I have more to send — though I won’t go into details, but I will have more stuff to send,” Shapps added.

Production Vs Politics

While optimistic about continuing support for Ukraine, Shapps acknowledged that “replenishment takes time where new contracts have to be laid to manufacture more weapons.”

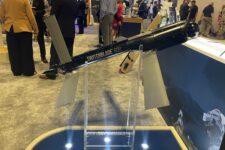

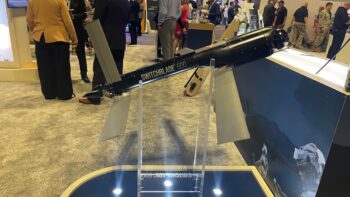

The need to get on contract was a major point of concern during October’s annual AUSA conference in Washington. There, munition production was a frequent topic, with Morten Brandtaeg, CEO of Norway’s Nammo, telling Breaking Defense that the munitions industry is at risk of “breaking its neck” if governments don’t put out longer, more reliable contracts.

Getting on longer contract, industry has argued, would come with more willingness to expand production sites. Single-location factories that manufacture items with no backup facilities or other substitute options create production shortfalls and leave no surge capacity to call on to meaningfully increase output.

Notably, a study from Washington-based CSIS identifies several US defense industrial sites where weapons that have been game-changers in the Ukraine war are built — like the Holston Army Ammunition Plant in Kingsport, Tennessee, and the Javelin ATGM plant in Troy, Alabama. And a voluminous GAO report from June demonstrates there is almost no category of US weapon system for which demand is not outstripping production rates. In other words, industry could expect a windfall if they are willing to invest their own money.

Bauer addressed this issue head-on, stating that NATO nations desperately “need the [defense] industry to ramp-up production at a much higher tempo.”

The “the just-in-time, just-enough economy that we have built together in the last 30 years” is not suitable for the realities of modern combat, Bauer argued, saying the system “led to higher prices, even before the war.”

Complicating the situation: Since Bauer’s comments, the conflict between Israel and Hamas kicked off, with the US rushing munitions to Israel — and in at least one case, diverting weapons intended for Ukraine towards Israel.

Speaking to the New York Times, one US official stated that in the case of artillery rounds a possible solution would that the two countries “may receive different variants of the ammunition to avoid overlap.” The United States could provide Israel precision-guided shells use against targets in a crowded urban area, the official stated as an example, while the cluster munition rounds that are already being sent to Ukraine may be more effective against positions located on a larger battlefield.

Although not directly related to Ukraine, shifts in politics and long-production times could also play a role in changing how neighboring Poland spends its money.

The Oct. 15 national election brought the pro-European Koalicja Obywatelska (Coalition Platform) back into power, displacing the Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice) party that took power in 2015.

Tomasz Siemoniak is expected to return as Defence Minister under the new government, and procurement decisions made in the past eight years could be reviewed or potentially even cancelled. There are also changes in the armed force’s leadership that will turn over again when the new government under KO leader Donald Tusk is formed.

Post-election horse-trading may take several months to sort out, meaning it could be well into next year before Poland addresses the issues of its continuing support for the Ukraine and its role in NATO. In meantime, the bottom of the barrel issue is not going away anytime soon.

Aaron Mehta in Washington contributed to this report.

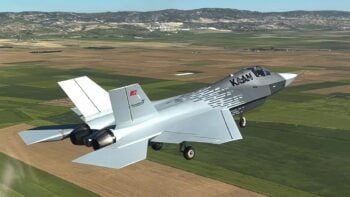

TAI exec claims 20 Turkish KAAN fighters to be delivered in 2028

Temel Kotil, TAI’s general manager, claimed that the domestically-produced Turkish jet will outperform the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.